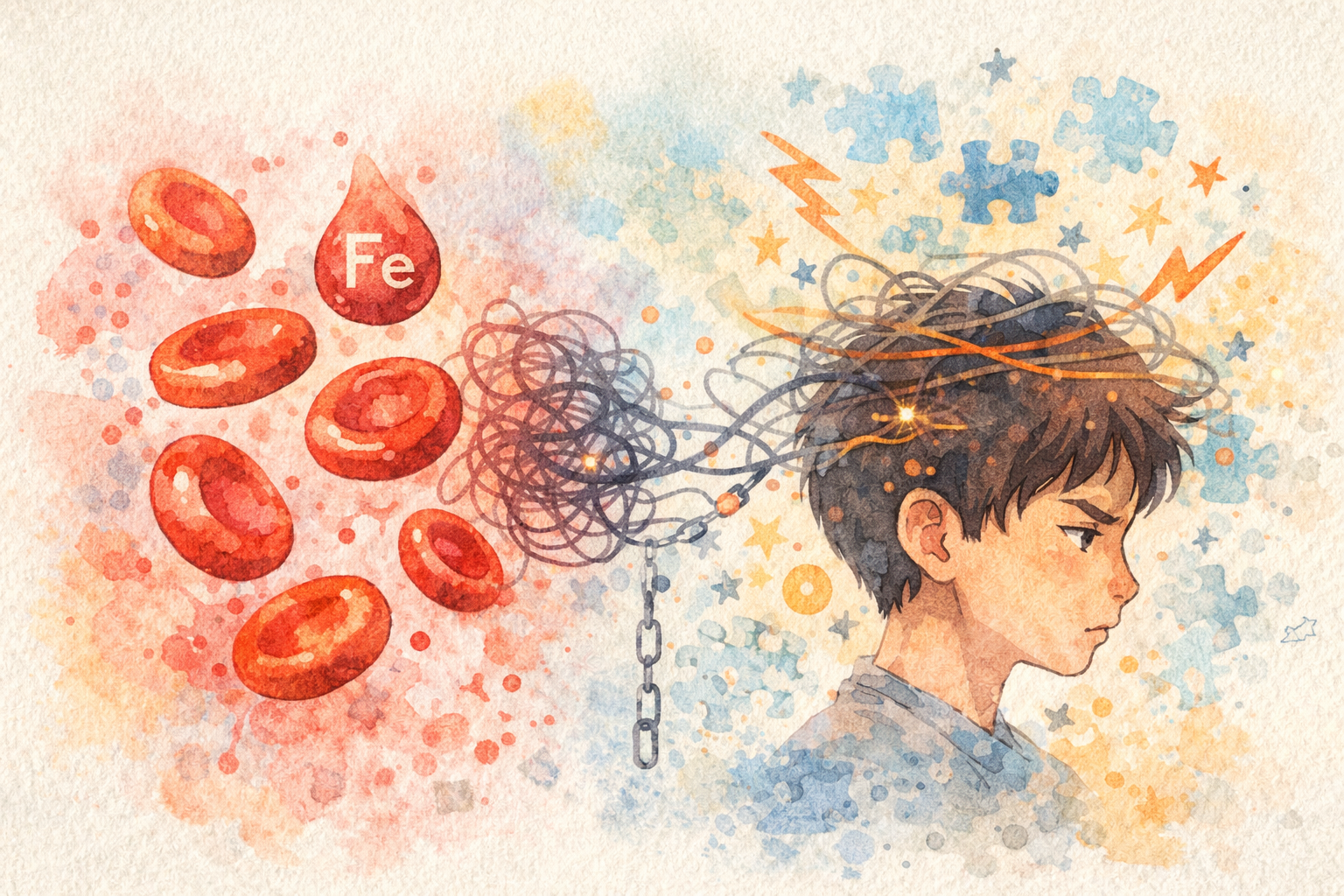

ADHD and Iron Deficiency: An Under-Recognised Biological Link

Could low iron affect ADHD symptoms? Learn about ferritin testing, diet, and evidence-based supplementation in Australia.

ADHD and Iron Deficiency: An Under-Recognised Biological Link

Research into attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has traditionally focused on behavioural symptoms, neurotransmitters, and genetics. In recent years, however, growing interest has emerged around nutritional factors, particularly iron status, as a potential modifier of ADHD symptoms and overall wellbeing.

Iron deficiency, especially low ferritin levels —which reflect reduced iron stores, does not cause ADHD. However, emerging evidence suggests it may contribute to symptom severity in some individuals or affect how well standard treatments are tolerated.

The Role of Iron in the Brain and ADHD

Iron is essential for several neurological processes that are relevant to attention, behaviour, and executive function.

Dopamine and catecholamine production

Iron is a required cofactor for tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. These neurotransmitters are central to brain circuits involved in attention, motivation, impulse control, and reward processing—systems already implicated in ADHD.

Low iron availability may therefore reduce the efficiency of these pathways, particularly in regions such as the prefrontal cortex and striatum.

Brain development and myelination

Adequate iron is necessary for myelin formation, which allows neurons to transmit signals efficiently. Iron deficiency—especially during childhood and adolescence—can impair myelination, potentially affecting processing speed, attention, and executive function.

Neurotransmitter regulation and emotional control

Iron also plays a role in broader neurotransmitter metabolism, influencing systems involved in mood regulation, emotional reactivity, and arousal.

Importantly, these effects can occur even in the absence of anaemia. Individuals may have normal haemoglobin levels while still having low iron stores.

Ferritin and ADHD: What the Research Shows

Most research examining iron status in ADHD focuses on serum ferritin, the primary marker of iron storage.

Lower ferritin levels in ADHD populations

Several observational studies and meta-analyses, particularly in children, have found that average ferritin levels are lower in ADHD cohorts compared with controls. This does not mean that most people with ADHD are iron deficient, but it suggests iron insufficiency may be more common in this population.

Symptom correlations (not causation)

Some studies report weak associations between lower ferritin levels and increased hyperactivity or inattention, though results are inconsistent and effect sizes are small. There is no evidence that low iron causes ADHD, and the relationship appears correlational rather than causal.

Ferritin is also an acute-phase reactant, meaning it can be falsely normal or elevated during inflammation or infection. For this reason, clinicians often interpret ferritin alongside other iron studies and clinical context.

Who May Benefit From Iron Testing?

Iron testing may be worth discussing with a healthcare professional for people with ADHD who also have:

Symptoms that may be consistent with low iron (non-specific)

Persistent fatigue

Cognitive “fog” or reduced concentration

Restless legs or disturbed sleep

Irritability or low mood

Dietary or medical risk factors

Vegetarian or vegan diet

Chronically low food intake or appetite suppression

Gastrointestinal conditions (e.g. coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease)

Long-term proton pump inhibitor use

Periods of rapid growth (children and adolescents)

Behavioural or treatment clues

Significant sleep difficulties

Poor tolerance of ADHD medications

Limited response to otherwise appropriate ADHD treatment

Addressing Dietary Iron: Australian Foods That Help and Hinder

If iron studies suggest low or borderline iron stores, dietary strategies are often considered alongside any medical treatment. Understanding the different forms of dietary iron and how absorption is affected can help guide these choices.

Well-Absorbed Sources of Heme Iron

Heme iron, found in animal-based foods, is absorbed far more efficiently than plant-based (non-heme) iron and is less affected by other components of the diet. Even relatively small servings can contribute significantly to iron stores.

Common Australian sources include:

Kangaroo meat, which is exceptionally high in iron and very low in fat, making it an efficient option for improving ferritin levels

Lamb, widely consumed in Australia and a reliable source of well-absorbed iron

Chicken liver and other organ meats, among the richest dietary sources of iron, though often eaten less frequently

Beef and other red meats, which provide consistently high amounts of heme iron and are staples in many diets

Including heme iron sources several times per week can provide substantial support for iron repletion, particularly for individuals with confirmed iron deficiency.

Non-Heme (Plant-Based) Iron Sources

Plant-based foods supply non-heme iron, which is absorbed less efficiently but still contributes meaningfully to total iron intake—especially for people who eat little or no meat.

Common Australian sources include:

Leafy green vegetables such as spinach

Legumes, including lentils, chickpeas, and beans

Soy-based foods such as tofu and tempeh

Iron-fortified breakfast cereals, which are a major source of dietary iron for many households

Absorption of non-heme iron improves significantly when consumed alongside vitamin C–rich foods (such as citrus fruits, berries, capsicum, or tomatoes), making meal composition an important consideration.

Foods and Substances That Inhibit Iron Absorption

Certain dietary components can reduce iron absorption by binding to iron in the gut. These include:

Tea and coffee, due to their polyphenol content

Calcium-rich foods or supplements, including large amounts of dairy

Phytates found in legumes and whole grains (though soaking, sprouting, or fermenting can reduce this effect)

To minimise interference, it is best to separate iron-rich meals or iron supplements from strong inhibitors by one to two hours. For example, iron supplements are better taken with water or juice rather than coffee, and dairy foods can be consumed at a different time of day.

Evidence-Based Iron Supplementation

When iron deficiency is confirmed through blood testing, supplementation may be recommended alongside dietary measures. Research in both general iron deficiency and selected ADHD populations informs current clinical practice.

Commonly Used Forms of Iron

In clinical settings, several oral iron formulations are commonly used:

Ferrous sulphate – the most extensively studied, widely available, inexpensive, and effective form

Ferrous fumarate and ferrous gluconate – often better tolerated and more palatable for some individuals

Iron bisglycinate – more expensive, but generally well absorbed and associated with fewer gastrointestinal side effects

The choice of formulation is often guided by tolerance, cost, and patient preference rather than large differences in efficacy.

Typical Dosing Guidance

Therapeutic dosing depends on age, body weight, and the severity of deficiency, and should be guided by a healthcare professional.

Commonly used regimens include:

Children: approximately 3–6 mg/kg/day of elemental iron

Adults: commonly 60–100 mg of elemental iron per day

Lower daily doses or alternate-day dosing are increasingly used, as they may improve absorption and reduce gastrointestinal side effects in some individuals.

Duration of Supplementation and Monitoring

Iron repletion is gradual. In most cases:

Iron supplementation is continued for 3–6 months

Ferritin and iron studies are often rechecked after 8–12 weeks to assess response

Treatment is typically continued beyond normalisation of haemoglobin to ensure adequate replenishment of iron stores.

Safety Considerations

Iron supplements should not be started without prior blood testing or medical advice.

Excess iron can be harmful, particularly in individuals without deficiency

Be vigilant for side-effects such as nausea, abdominal discomfort, constipation, and dark stools

What Changes Might Be Expected?

When iron deficiency is present, correction may be associated with:

Improved sleep quality

Reduced restlessness

Modest improvements in attention or concentration

Improved tolerance or consistency of response to stimulant medication

Responses vary, and not everyone will experience noticeable cognitive or behavioural changes.

The Takeaway

Iron plays an important role in brain development, myelination, and dopamine synthesis.

In Australia, Medicare-funded pathology testing makes iron studies accessible when clinically indicated. For individuals with ADHD who have symptoms or risk factors consistent with iron deficiency, checking ferritin and a full iron panel is a reasonable, evidence-based step.

Iron supplementation does not treat ADHD itself. However, identifying and correcting iron deficiency may improve overall wellbeing and, in some individuals, modestly support attention, sleep, or response to ADHD treatments.

Nevertheless, evidence-based medication remains the most effective treatment for ADHD. At Kantoko, our experienced clinicians provide personalised ADHD medication management to help you find the right treatment plan.

Ready to start your ADHD Journey? Get Started with Kantoko today.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment options.